The cosmos’ annual gift to sky watchers, the Geminids Meteor shower, will peak on Dec. 13-14 this year.

During peak activity and perfect weather conditions, which are rare, the Geminids produce approximately 100-150 meteors per hour for viewing. However, this year a waning gibbous moon will make it harder to view most of the shower, resulting in only 30-40 visible meteors per hour at the peak in the Northern Hemisphere, depending on sky conditions. But the Geminids are so bright that this should still be a good show.

Bill Cooke, lead of NASA’s Meteoroid Environments Office at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, suggests sitting in the shade of a house or tree while also maintaining a view of the open sky to alleviate moonlight interference.

The meteor shower is coined the Geminids because the meteors appear to radiate from the constellation Gemini. According to Cooke, meteors close to the radiant have very short trails and are easily missed, so observers should avoid looking at that constellation. However, tracing a meteor backwards to the constellation Gemini can determine if you caught a Geminid (other weaker showers occur at the same time).

Gemini does not appear very high above the horizon in the Southern Hemisphere, resulting in viewers only seeing approximately 25% of the rates seen in the Northern Hemisphere, which is between 7-10 meteors per hour. Sky watchers from the Southern Hemisphere are encouraged to find areas with minimal light pollution and look to the northern sky to improve their viewing opportunities.

The Geminids start around 9 or 10 p.m. CST on Dec. 13, making it a great viewing opportunity for any viewers who cannot be awake during later hours of the night. The shower will peak at 6 a.m. CST on Dec. 14, but the best rates will be seen earlier around 2 a.m. local time. You can still view Geminids just before or after this date, but the last opportunity is on Dec. 17 – when a dedicated observer could possibly spot one or two on that night.

For prime viewing, find an area away from city and streetlights, bundle up for winter weather conditions, bring a blanket or sleeping bag for extra comfort, lie flat on your back with your feet facing south, and look up. Practice patience because it will take approximately 30 minutes for your eyes to fully adjust and see the meteors. Refrain from looking at your cell phone or other bright objects to keep your eyes adjusted.

The show will last for most of the night, so you have multiple opportunities to spot the brilliant streaks of light across our sky.

So where does this magnificent shower come from? Meteors are fragments and particles that burn up as they enter Earth’s atmosphere at high speed, and they usually originate from comets.

The Geminid shower originates from the debris of 3200 Phaethon an asteroid first discovered on Oct. 11, 1983, using the Infrared Astronomical Satellite. Phaethon orbits the Sun every 1.4 years, and every year Earth passes through its trail of debris, resulting in the Geminids Shower.

Phaethon is the first asteroid to be associated with a meteor shower, but astronomers debate its exact classification and origins. Phaethon lacks an icy shell (the staple characteristic of a comet), but some consider it a “dead comet” – suggesting it once had an icy shell that melted away. Other astronomers call it a “rock comet” because Phaethon passes very close to the Sun during its orbit, which theoretically results in heating and cracking that creates debris and dust. The bottom line is Phaethon’s exact origins are still a mystery, but we do know it’s the Geminids parent body.

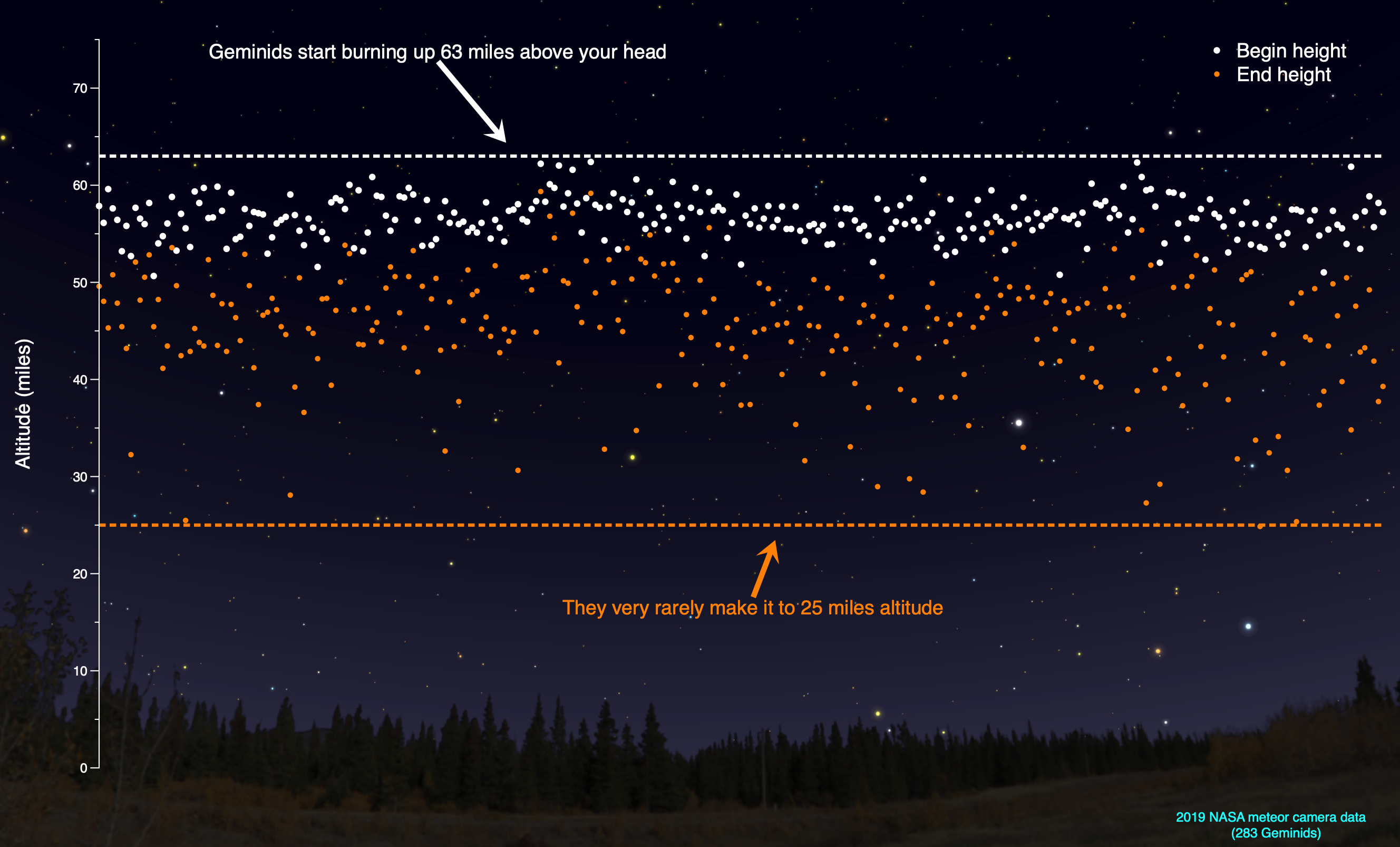

Geminids travel 78,000 miles per hour, over 40 times faster than a speeding bullet, but it is highly unlikely that meteors will reach the ground – most Geminids burn up at altitudes between 45 to 55 miles.

In addition to sky watching opportunities, meteor videos recorded by the NASA All Sky Fireball Network are available each morning to identify Geminids in these videos – just look for events labeled “GEM.”

And, if you want to know what else is in the sky for December, check out the video below from Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s monthly “What’s Up” video series:

Happy stargazing!

by Lane Figueroa

I’m curious about meteorites and would like to see them because I’m interested in the stars the sky I like to watch the stars sometimes I see a sign made of stars in the sky a hammer I also see satellites in the sky it separates itself from other stars and from other stars